On the occasion of International Women’s Day, we present an article dedicated to some of the female artists and creators of the Belle Époque that, over time, have been forgotten, since mainly male artists have stood out, but that, even so, have left their mark on the history of art.

The women artists of the Belle Époque became, for the most part, icons of emancipation and freedom.

In the 19th century, the new Republic, symbolised by Marianne, still denied women any civic rights and therefore refused to make them equal to men. Often confined to the domestic sphere, Eve’s daughters remained under the guardianship of their fathers or husbands all their lives, who, until 1965, could authorise them, or not, to work. Often considered to be muses, many of them practised painting and sculpture with great talent. Nevertheless, women generally occupy only a small place in books and in our memory, which for centuries has been shaped exclusively by men.

Often referred to as the “forgotten ones of art history”, questioning the place of women in the artistic sphere is ultimately a question of the role of half of humanity in this field.

Women artists of the Belle Époque became, for the most part, icons of emancipation and freedom. Generally living from their work and participating in Parisian social life, they integrated themselves into a world which, at the time, was still considered exclusively male. This was particularly true of the Impressionist Berthe Morisot, who wrote: “I will only gain my independence through perseverance and by openly expressing my intention to emancipate myself”. Her art, full of audacity and modernity, will be defined by her intimate and familial representations. The woman who signed her works with her maiden name throughout her life was also keen to depict a theme that is rarely seen in art, that of fatherhood, as in the work Eugène Manet and his daughter in the garden at Bougival.

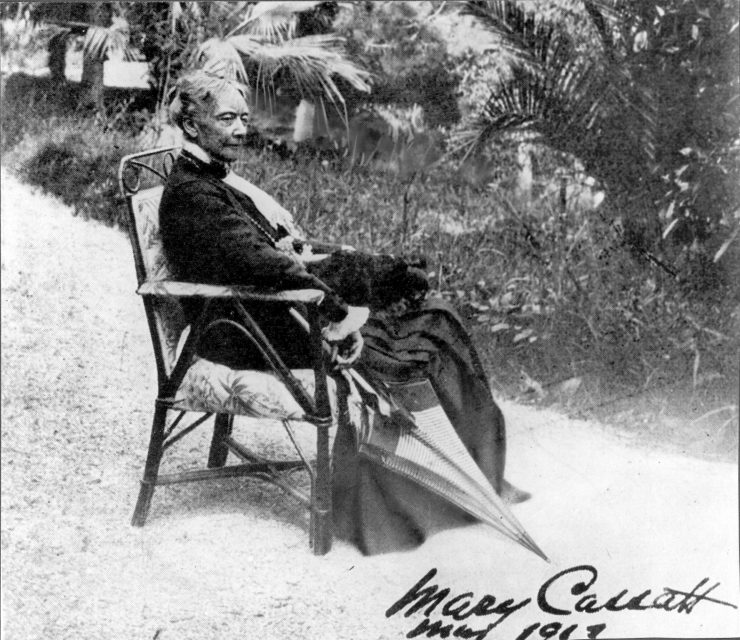

Another model of emancipation and autonomy, Mary Cassatt imported the Impressionist movement to the United States, where it developed. Her success in her home country enabled her to raise funds for the feminist suffragette movement. Her intimist works, illustrating strong and confident women, reflect the image she wishes to project. She decided to keep her freedom all her life by renouncing marriage and never had children.

Among them, we should also mention the famous sculptor Hélène Bertaux who, coming from a family of artists, fought all her life to offer women access to artistic training, which had been denied to them until then. This struggle led to the opening of a modelling workshop in Paris dedicated to women sculptors, the opening of the École des Beaux-Arts to women and, from 1903, the possibility of participating in the Prix de Rome.

The great painter Marie Vassilieff, a pupil of Matisse, followed in Bertaux’s footsteps by opening the Vassilieff Academy in Montparnasse, a place of learning and creative freedom for artists, men and women, from all over the world. Among his students were names such as Chagall, Zadkine, Orloff and Maria Blanchard. A true pioneer of the avant-garde, the Russian artist developed a style influenced by cubism as well as by primitive and naive art. She was also very close to Olga Sacharoff, a Georgian artist who arrived in Paris at the beginning of the 20th century, and who made a name for herself with her pastel-coloured landscapes, often with dreamlike, calm and magical features.

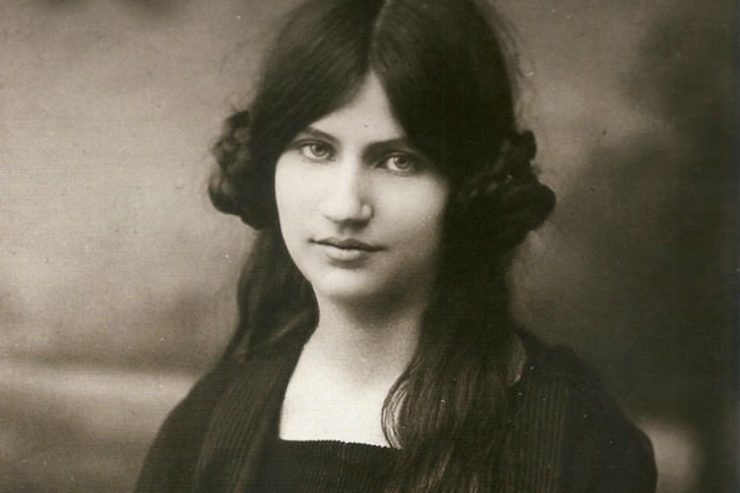

Other private academies, such as the Colarossi or the Julian, were springboards for the careers of artists. Among the most famous was Camille Claudel, who declared “I cry out for freedom“. Her sculptures, which tend to project pure emotion, will mark the history of art by the skilful use of imbalance, as well as by the passionate violence of her scenes, often linked to the theme of destiny from which one cannot escape. Jeanne Hébuterne, another pupil of Colarossi and described by her contemporaries as an intelligent woman with character and talent, devoted her short career to learning about light and colour in her portraits and self-portraits. In addition to painting, she distinguished herself through photography, jewellery and clothing.

Other figures also gained power at this time. These included the collectors and patrons Peggy Guggenheim and Helena Rubinstein, as well as the French gallery owner Berthe Weill, who became one of the greatest advocates of the French avant-garde. Modigliani, Picasso and the famous Emilie Charmy were the artists that “little mother Weill”, as Raoul Dufy called her, defended on the French and international art scene. The latter, who left a portrait of her patroness to posterity, was characterised by her desire to transcend “feminine art”. Whether in her subjects or in her compositions, Emilie Charmy will mark her work with a frank, thick and elegant touch.

This period of intense production also marked a break in the style of representations. Suzanne Valadon, who often appears in the works of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, was a self-taught painter who found success during her lifetime. She offered a new vision of femininity in her works, through the prism of a skilled painter, who suppressed the established canons of beauty for centuries. Her works depict the everyday life and bodies of women, often in brothels, in their crudest and most human aspects. The Danish artist and portraitist Gerda Wegener interprets the female figure in its strongest and most independent aspect. She was an illustrator for famous magazines such as Vogue, and the author of the controversial work, Lily, which depicts her husband Einar Mogens, who is credited with being the first man to undergo multiple surgeries to become a woman. Marie Laurencin‘s pastel-coloured female figures made her one of the few representatives of the Cubist movement. Nevertheless, far from following the path set out by the male artists of the movement at the time, the pupil of the painter and pastellist Madeleine Lemaire made the difference thanks to her elegant aesthetic with curvilinear forms.

The fight for recognition of their work, at a time when repression against women was at its height, made these and all the other women not mentioned in this article, icons of an era of intense creation and aesthetic revolution.