What do painting, photography and film have in common? These three fields are capable of creating unique aesthetics, telling fascinating stories and instilling strong emotions. Indeed, whether for reasons of remembrance, homage, admiration or propaganda, the need to leave a mark through images seems to be constant throughout history.

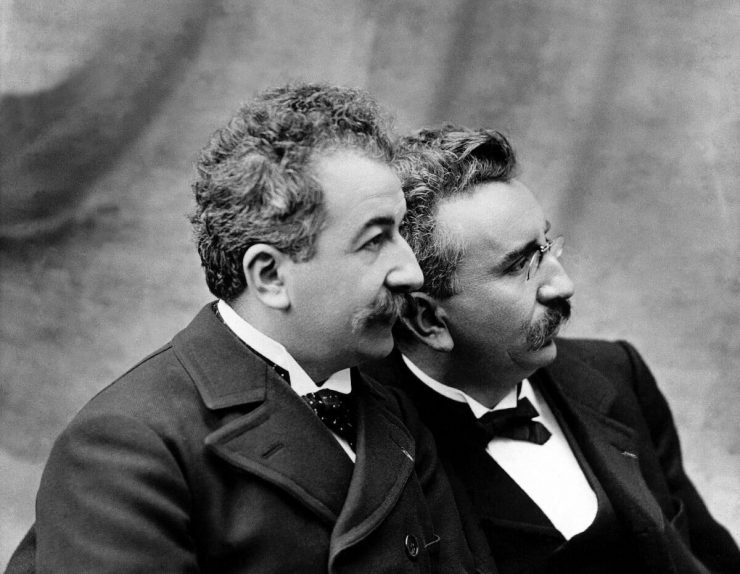

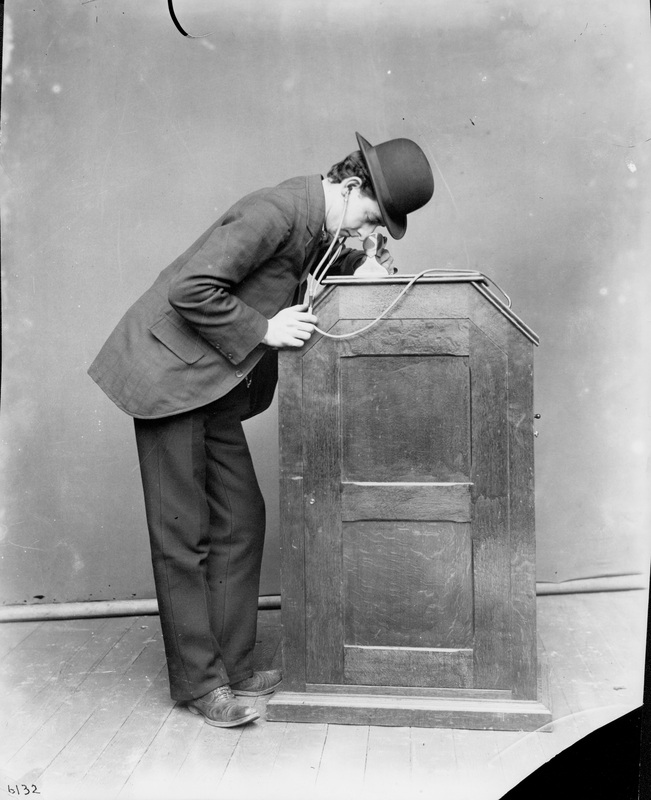

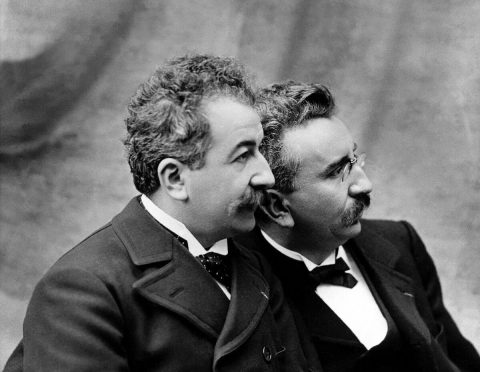

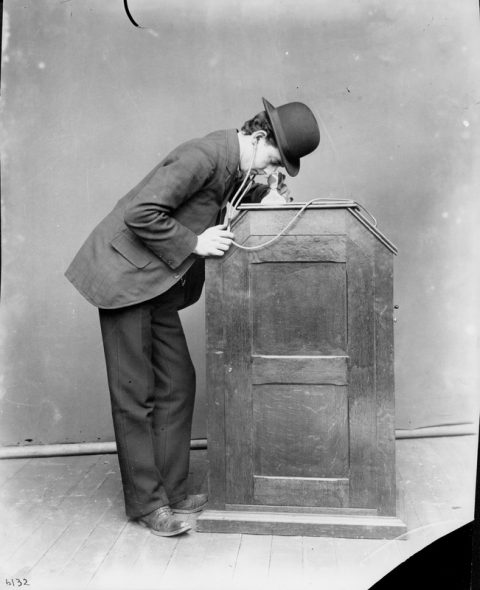

The nineteenth century saw a number of technical innovations that profoundly changed artistic practice and the way in which the world was viewed. While photography now made it possible to capture scenes instantaneously, painting put aside its quest for realism and began to develop new theories on what photographs did not yet have: colour. At the same time, research into visual processes that tended to retranscribe movement intensified. In 1882, Etienne Jules Marey invented chronophotography. A few years later, in 1890, Thomas Edison developed the kinetograph. However, the name that would go down in history was that of the Lumière brothers. At a time when Impressionism was gaining strength, Auguste and Louis introduced the world to the cinematograph in 1891. This was the birth of the 7th art.

Regarded as a new aesthetic medium in its own right, cinema soon shared the same artistic trends and movements. Some directors therefore paid tribute, sometimes subtly and other times more directly, to the great artistic masterpieces.

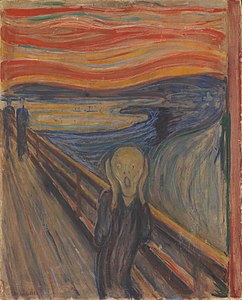

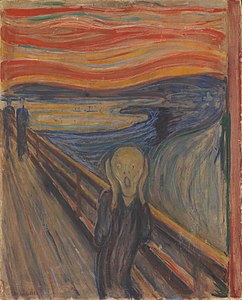

German Expressionism is characterised by figurative features with exaggerated distortions and bold colours to bring the emotions depicted, such as fear or anxiety, to a climax. In Edvard Munch’s The Scream, the ambiguous, genderless figure is almost disfigured by terror and anguish. This is underlined by the red and yellow tones of the sky, synonymous with chaos. A few years later, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau directed what was to become one of the pillars of horror cinema, Nosferatu. The film, which features a vampire, takes up the aesthetics of the monstrous, whether through the character’s disturbing physique or through his moral values. The framing, similar to the compositions in paintings, plays on the viewer’s imagination and hints at the threat posed by Count Orlock. The Expressionist-inspired aesthetic has endured over time. In 1996, Wes Craven directed the film Scream, in which the assassin embodies this confused energy. It is through his emblematic mask that the character, whose identity is reduced to nothing, inspires strong emotions.

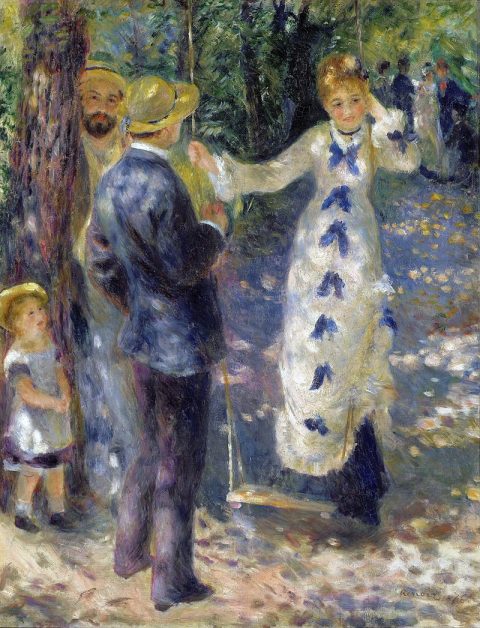

Some filmmakers draw direct inspiration from the works of painters. This is particularly true of Jean Renoir, son of the famous impressionist Pierre Auguste Renoir. A true admirer of his father, Jean never ceases to pay tribute to him. In Une partie de campagne, released in 1946, the director brought to life the work La balançoire, painted in 1876. This same film was recorded on the banks of the Loing, a river that inspired some of the artist’s most beautiful works.

In 2010, Martin Scorsese produced the thriller Shutter Island, in which a detective with a troubled past investigates the disappearance of patients from a psychiatric hospital. The main character, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, arouses a certain paranoia because of his psychological state. Once he arrives on the scene, he starts seeing his dead wife. In one of the scenes, Scorsese decides to make reference to Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss, which aesthetically implies the desire and instability of the marriage that the two characters have built up. The work, representative of the Viennese Secession, comes from Klimt’s golden period, when he painted a self-portrait with Emilie Flöge, his muse and partner.

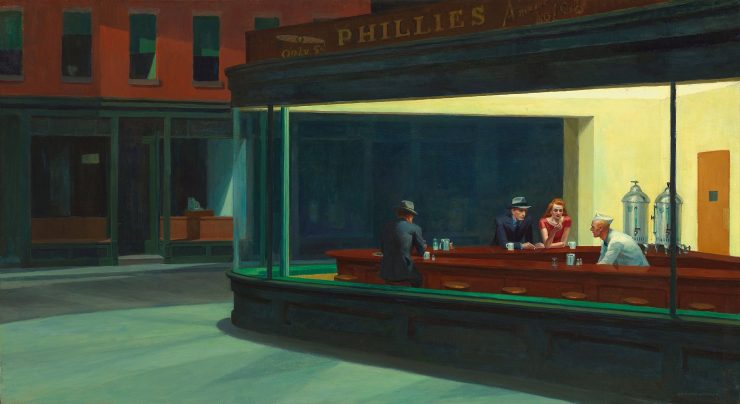

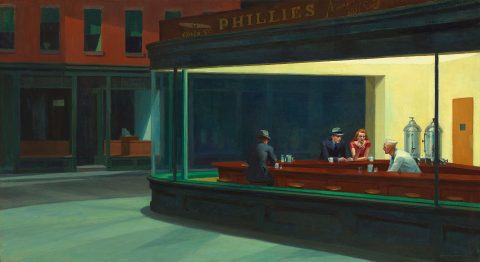

The American Edward Hopper is also an intense source of inspiration for filmmakers. Nighthawks illustrates the front of a café in the middle of the night. The four figures around the bar are placed next to each other. However, the lack of expression and the rigidity of the lines emphasise the emotional distance between them, representing a sense of isolation devoid of hope. Herbert Ross repeated this composition in 1981 in Pennies from Heaven. The story, set during the Great Depression in the United States, details the life of a struggling sheet music salesman who struggles to connect with those around him.

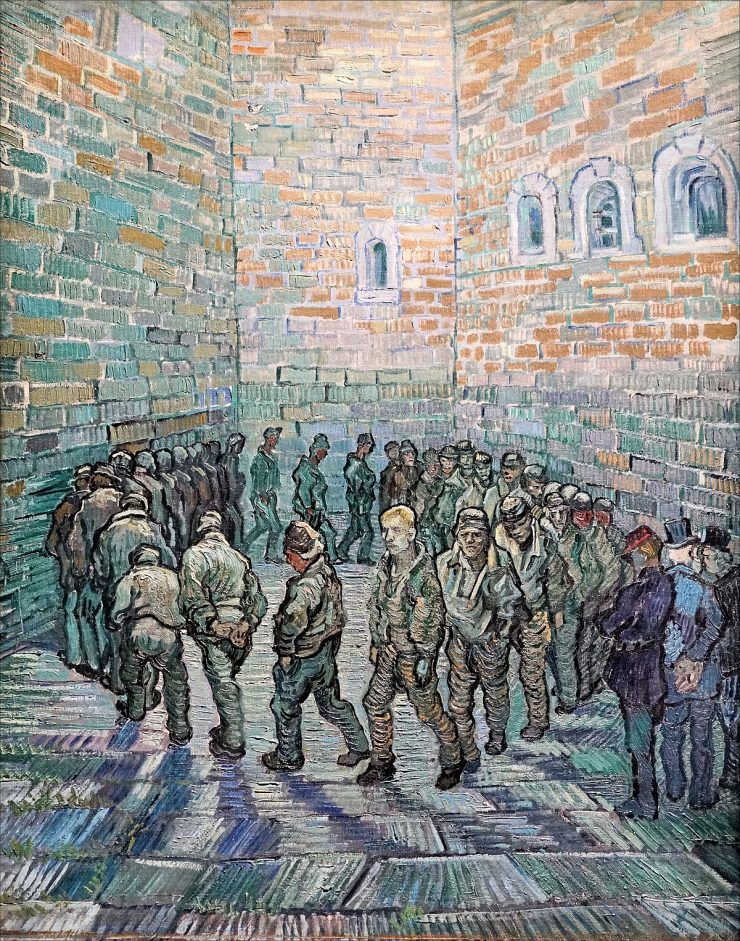

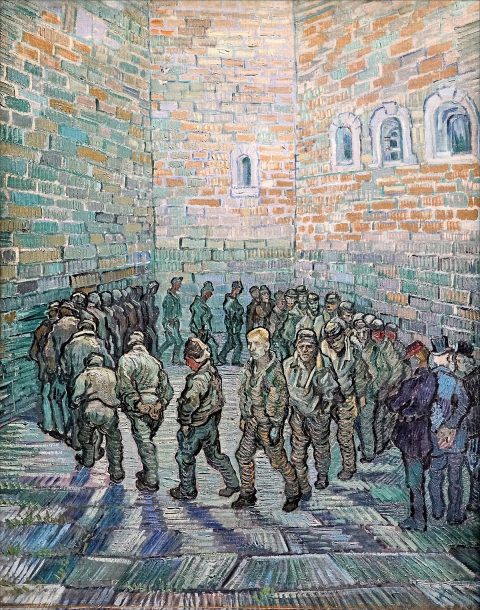

This despair is also perceptible in A Clockwork Orange. Released in 1972, the film reveals a dark portrait of human nature in an attempt to determine the origins of evil. Alex DeLarge, the protagonist, is imprisoned for committing sadistic crimes. He undergoes experimental treatment designed to cure brutal impulses. In the prison yard, the inmates march endlessly in circles, creating a claustrophobic and dehumanising atmosphere that never ends. Vincent Van Gogh, for his part, depicted The Prisoners’ Round at the time when he was voluntarily hospitalised at the Saint Rémy de Provence sanatorium in 1890. Through his painting, the artist illustrates an action that seems perpetual and aimless.

Diane Arbus is famous for her photographs of marginalised and unusual people. In 1967, she immortalised Cathleen and Colleen Wade, twin sisters aged seven. The photograph, which has now become famous, is reminiscent of the twins who haunt the corridors of the Overlook Hotel. This hotel, imagined by Stanley Kubrick in The Shining (1980), is the scene of unexplained events that will drive its caretaker mad.

While painting and photography have been anchors for cinema, with new movements such as pop art, the tide is turning. Known for its colourful, garish style, this trend was mainly inspired by advertising and the theme of mass production. Its artists, each in their own way, represent a modern, changing world through images that are familiar to all. Marilyn Monroe and Audrey Hepburn are clear examples. These iconic Hollywood figures fascinated the greatest artists of the 20th century, including Andy Warhol, who painted their portraits in a range of colours. Today, Natan Elkanovich and Antonio de Felipe still use these icons in their representations. Uri Dushy, Masaya and Alec Monopoly, all three of whom can be seen in the exhibition KHRÔMA. The Emotional Universe of Colour, use Disney characters, turning world-famous characters into unique works of art.

DID YOU KNOW

– The director, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, based his film freely on the novel Dracula, published by Bram Stocker in 1897, even though he had not paid the royalties. When the film was released in 1922, the writer’s widow brought a lawsuit against the production, which she won. The ruling required the production company to destroy all copies of Nosferatu. However, this penalty was never enforced.

– The Scream, which Edvard Munch painted in 1895, was sold at auction in 2012 for $120 million. This event gave it the title of the most expensive work in the world. This title was taken away from him the following year, when Francis Bacon’s Three Studies of Lucian Freud was sold.

– Two of the four versions of The Scream were stolen. The first in 1994 from the National Gallery in Oslo and the second in 2004 from the Munch Museum in the same city. They have now been recovered.