The new exhibition of the Museu Carmen Thyssen Andorra, Made in Paris. The Generation of Matisse, Lagar and Foujita, aims to be an eclectic and relevant sample of what the French capital represented artistically during the Belle Époque. The Paris of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which often gave rise to the bohemian and elegant image of the City of Light today, was not only a place of creation and welcome for artists from all over the world, but also one of the embodiments of modernity.

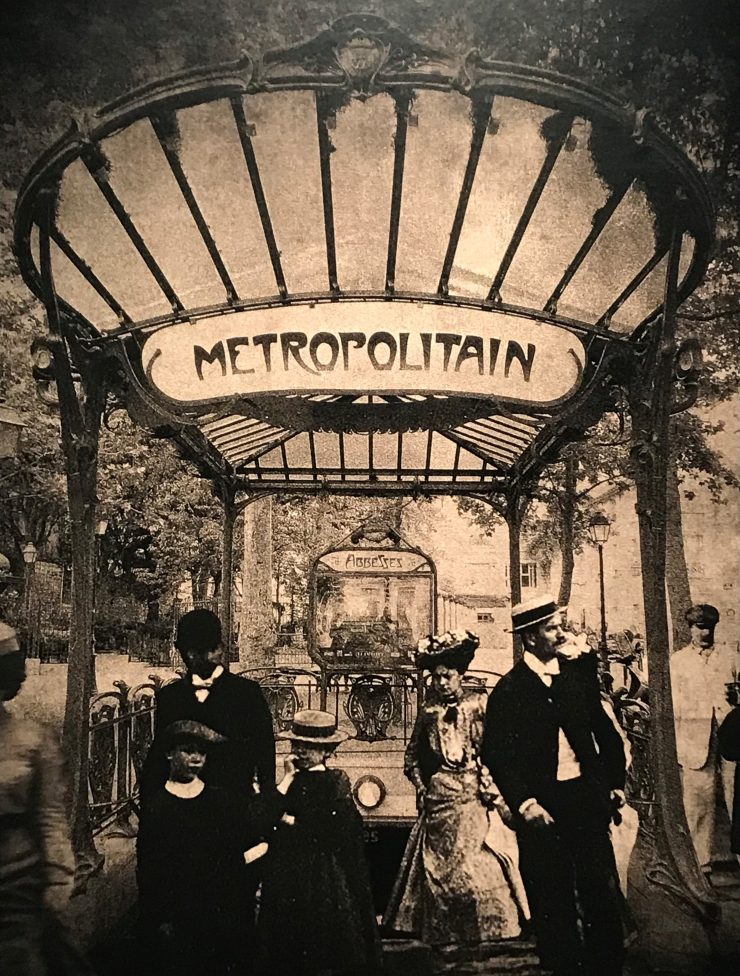

Like this exhibition, we suggest that you fasten your seatbelts for a trip underground, in the famous Parisian Metropolitain.

The French 19th century was characterised by instability and change. Between the establishment of two empires, the restoration of two monarchies and the setting up of three republics in just one hundred years, it was also a time when industrialisation and modernisation were taking hold.

While Eugène Viollet-de-Duc was restoring Notre-Dame de Paris and Baron Haussmann was building the great Parisian boulevards that we still know today, Fulgence Bienvenüe and Edmond Huet proposed the first metro lines. Work began in 1898, and in 1900, with the Universal Exhibition, the trains welcomed their first passengers.

Despite the modernity of this pharaonic project, Parisians were not convinced and many viewed the metro with contempt. This is why the authorities imposed discretion on the builders, both for the works and aesthetically speaking. In the end, the Metropolitain’s emblematic entrances were created by Hector Guimard in the Art Nouveau style, characterised by its fir-green wrought-iron arabesques, which blended skilfully into the urban décor and became one of the city’s many icons.

Over the following decades, and in response to the success of the metro, the lines multiplied and served every corner of the city. However, in 1939, as the Second World War began, men were sent to the front. The lack of workers forced those in charge of the Paris metro to restrict the activity of the trains and close stations temporarily or permanently.

Following the conflict, these ghost stations, which do not appear on any map, fall into oblivion while others are reborn.

The famous Porte des Lilas, which was never opened to the public, was the bohemian and romantic setting of The Fabulous Desteny of Amélie Poulain under the name of Abbesses station. While the Arsenal station, which is now a storage facility, is remembered by the French as the location of the 1965 film La Grosse Caisse.

As unusual and timeless places, they also become playgrounds for contemporary artists. This is notably the case of the artist Guy-Antoine Bonhomme who, in 1983, transformed the Croix-Rouge station into a beach that travellers could enjoy for a few seconds by speeding past.

Finally, other stops, such as Saint-Martin or Gare du Nord station, have utilitarian roles. The former is home to the Salvation Army and the latter is now a training ground for future Parisian metro drivers.