Synonymous with finesse and elegance, Japonism was a trend that had a profound influence on Western artistic activity in the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

While production in Western Europe followed models that had always been fixed by the Academy, modernity, technological evolution and the economic stability that characterised the 19th century pushed some artists to renew the aesthetic field. This rupture, better known as the avant-garde, found its richness in a multitude of sources of inspiration. Among them was Japan, so foreign to Western art, which became one of the keystones of this new chapter in history.

A veritable wave of exoticism, Japonism swept through Europe from 1853 onwards, at the moment when Japan emerged from its isolationist policy that had cut it off from the rest of the world for over two centuries. The opening of the borders led to trade and exchange, and Japanese culture made its appearance at the 1867 Paris Universal Exhibition. Fashion was launched. Between spirituality and simplicity, the French, and more particularly the Parisians, happily adopted these objects, silks and fabrics from the other side of the world.

This new aesthetic also seduced the most famous artists of their time. James McNeill Whistler discovered Japanese prints in a Chinese tea room in London and, as a result, became one of the greatest collectors, along with James Tissot and Edgar Degas, of Japanese objects. These were to be found in his works, as can be seen in The Little White Girl, 1864 – 1865. The great Claude Monet fell in love with Japanese motifs when he saw them on a wrapping paper in a spice shop in Holland. Later, in Giverny, the artist’s garden would illustrate his love for the land of the rising sun. Many historians will argue that without this influence, Impressionism and, later, the avant-garde, would not have been born.

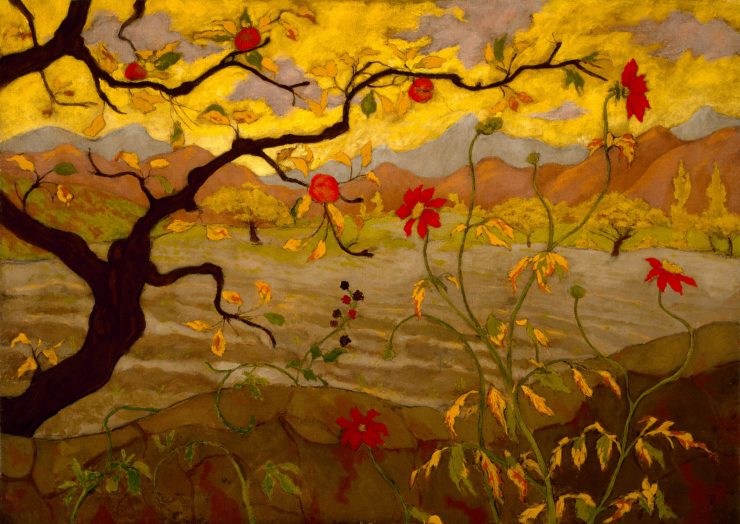

The representatives of Nabism, another important trend of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, were also its spokesmen. Characterised by flatness, vibrant colours and stylisation, the artist Paul Ranson was nicknamed “The Nabi who is more Japanese than the Japanese Nabis”. Pierre Bonnard, on the other hand, was called “the Nabi very Japonard”.

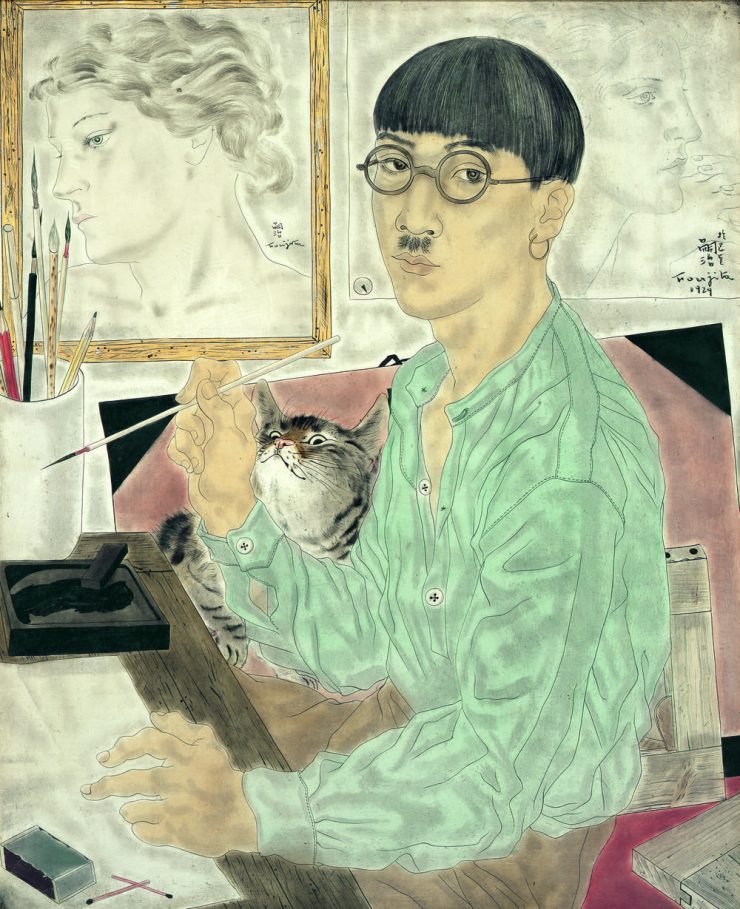

Contributing greatly to modern art and, by extension, to Paris’ reputation, the French capital also welcomed a large number of Japanese artists. This was particularly true of the whimsical Tsuguharu Foujita, who spent more than half his life in France. His nudes, with their milky skin and finely executed contours, were the perfect synthesis of Eastern and Western art. Mixing ink and oil, the painter was characterised by his calligraphic touch and his calm and minimalist compositions.

Foujita embodied the link between two worlds, which made him an artist in the image of Japonism: an artist who was neither totally French nor totally Japanese.