The artistic signature is far more than a discreet stroke in the corner of a canvas. It’s a mark of identity that has accompanied humankind from the earliest artistic manifestations to the global market of contemporary art.

In Prehistory, specifically in european paleolithic cave art, we don’t find human figures as protagonists, but rather symbolic representations of hands in positive and negative. These hands imprinted on cave walls functioned as marks of presence and can be understood as a primitive form of authorship.

In Egypt and Mesopotamia’s civilizations, the first clear systems of personal identification appear. Scarabs and other seals were used to authenticate documents and objects with administrative, religious, and diplomatic functions. At the same time, cylindrical seals, invented around 3.500 BCE in Susa, in southeastern Iran, made it possible to imprint scenes and inscriptions onto wet clay. Although their primary use was administrative or as the signature of an authority, they were also worn as jewelry and amulets with magical functions. In this context, an interest in recording authorship began to emerge, but this reality was evident only among the wealthy classes and patrons, not among artisans.

During the Middle Ages, anonymity continued to dominate artistic production. Workshops and guilds produced collective works in which individual authorship was diluted. In this period, the rubric, understood as the distinctive mark composed of lines, curves, or symbols that accompanies a signature emerged as a substitute for earlier Latin formulas, becoming a personal element attached to documents. Official seals and the monograms of nobles and popes guaranteed authenticity, while in art the creator’s invisibility prevailed over the prominence of the patron.

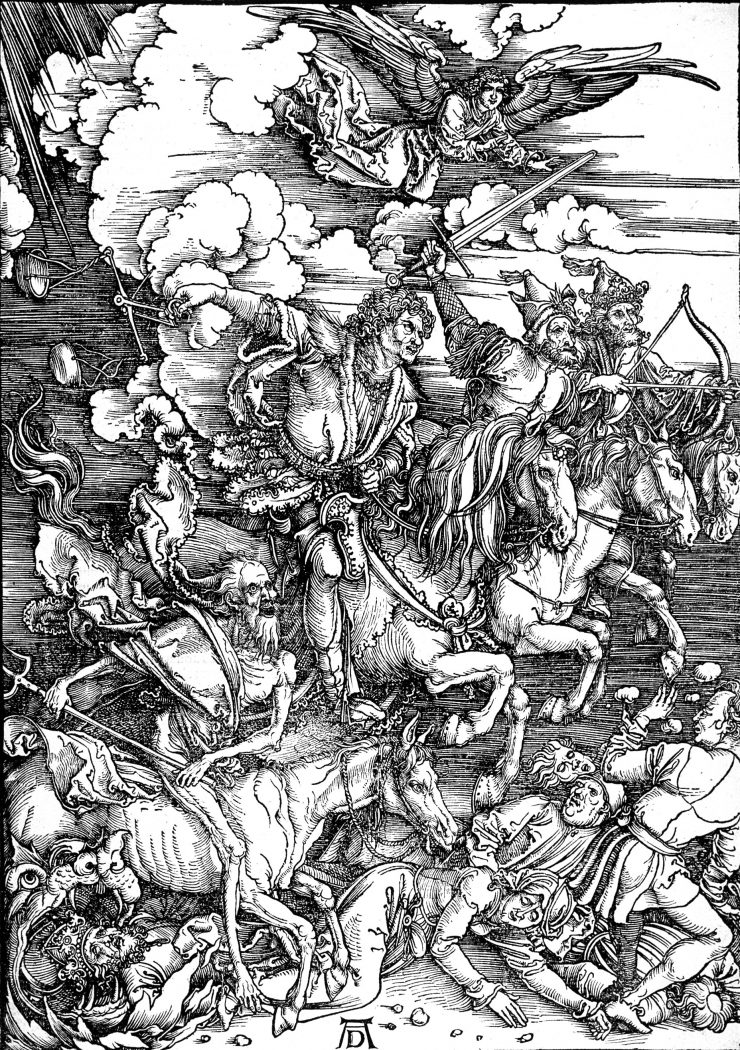

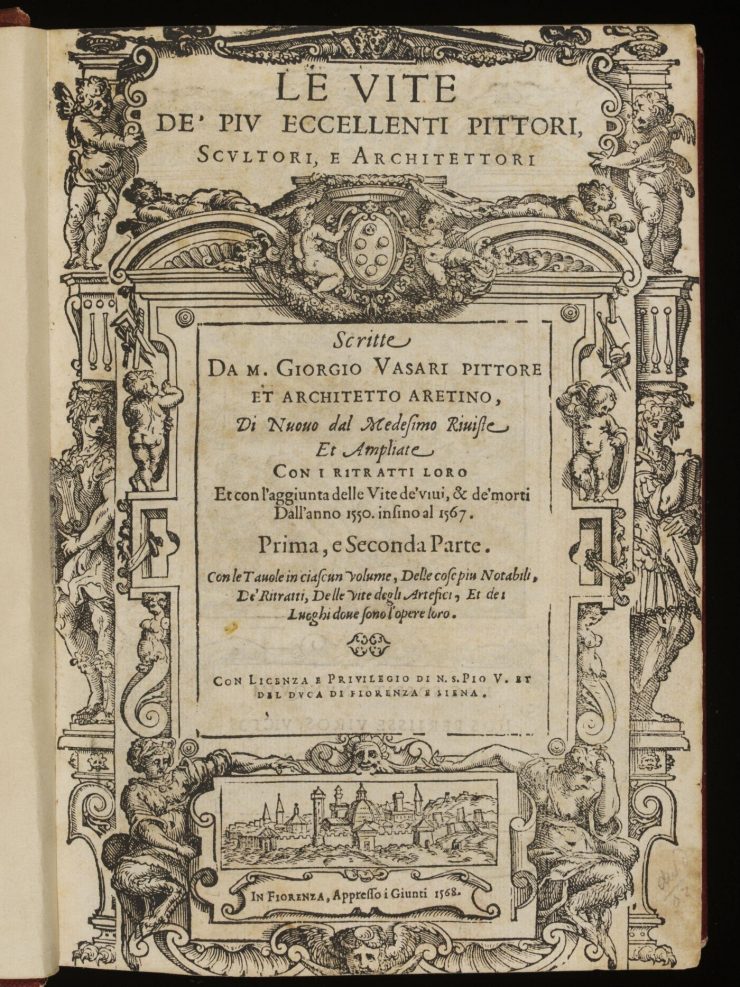

The Renaissance marked a decisive turning point in the recognition of the author. The artist ceased to be regarded as a mere craftsman and became an intellectual and a social figure. The signature was transformed into a gesture of pride and a claim of authorship. Michelangelo signed the Pietà in Rome, Dürer popularized the use of monograms, and Giorgio Vasari consolidated the importance of the artist’s name as a historical value with the publication, in 1550, of Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects.

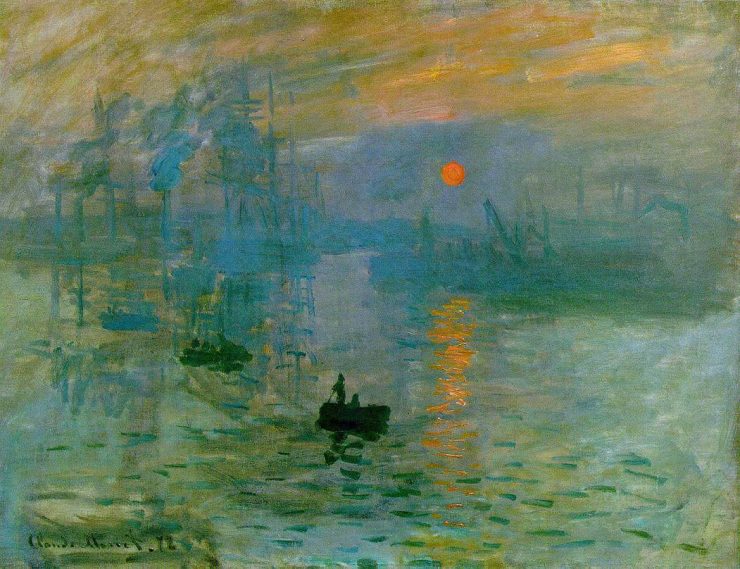

With the arrival of modernity, the signature acquired unprecedented prominence. It became a seal of prestige that certified authorship and, at the same time, a passport to the art market and social recognition. The signature ceased to be a merely administrative element and was transformed into a personal brand that directly linked the artwork to the artist’s name. Collectors and institutions sought signed works because the author’s name was synonymous with quality and authenticity.

A clear example is Eugène Delacroix, a romantic painter who signed his works with pride, reinforcing the idea of the creative genius and consolidating his reputation in the art market. Later, in Post-Impressionism, we find artists such as Vincent van Gogh, who chose to sign with their first name. This decision conveyed closeness and authenticity, and today his signature is inseparable from the symbolic and economic value of his works.

The twentieth century brought the artistic signature into new dimensions. Figures such as Picasso, Miró, and Dalí fully integrated it into their visual identity, turning it into an inseparable element of their creative language. At the same time, Andy Warhol elevated it to the status of a brand, linking it to mass consumption and pop culture, demonstrating how the signature could function as a symbol of commodification and a cultural icon.

Ultimately, the artistic signature has evolved from a primitive mark into a global brand. It is a bridge between creator and viewer, a symbol of recognition and memory, but also a field of dispute over visibility, commodification, and authorship. Every signature, every absence, and every forgery speaks to us of power, identity, and the struggle to be recognized in the history of art.