Mysterious and elusive, dreams are certainly one of the most intimate experiences, unique to each individual. Paradoxically, Western artists have always depicted these states, revealing to the public these dreamlike phenomena for which perception and interpretation have evolved over time.

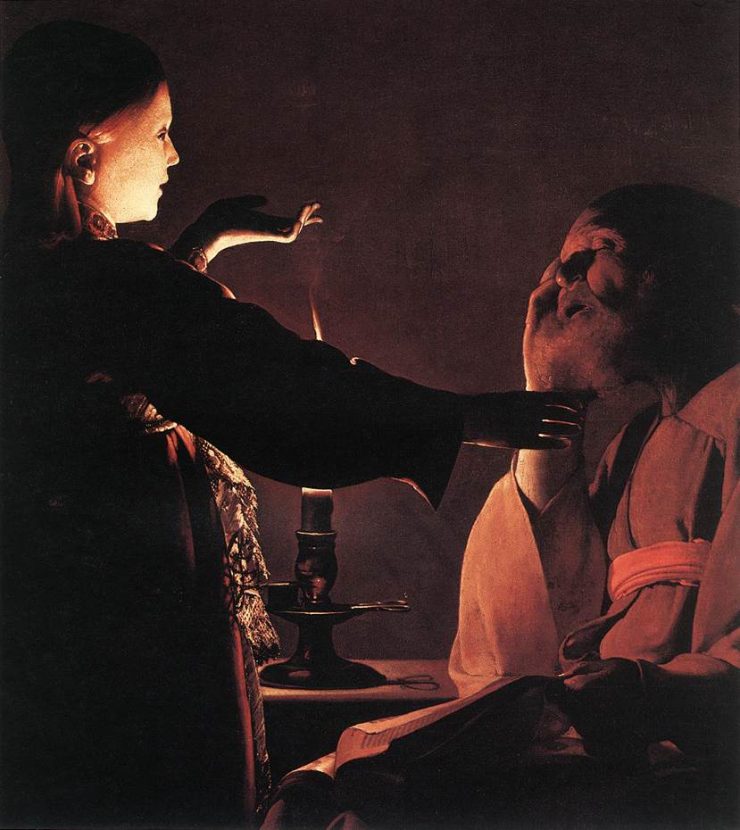

Dreams were originally associated with prophecy, oracles and announcements. Dreams are the perfect conduit for divine messages, as shown by the various illustrations of the dreams of biblical characters, such as that of Saint Joseph, in which an angel orders him to marry Mary, flee to Egypt and return when Herod dies. The dream is therefore a valuable source of information and is necessarily delivered to a person who is worthy of passing it on. The dream thus embodies access to a certain form of truth.

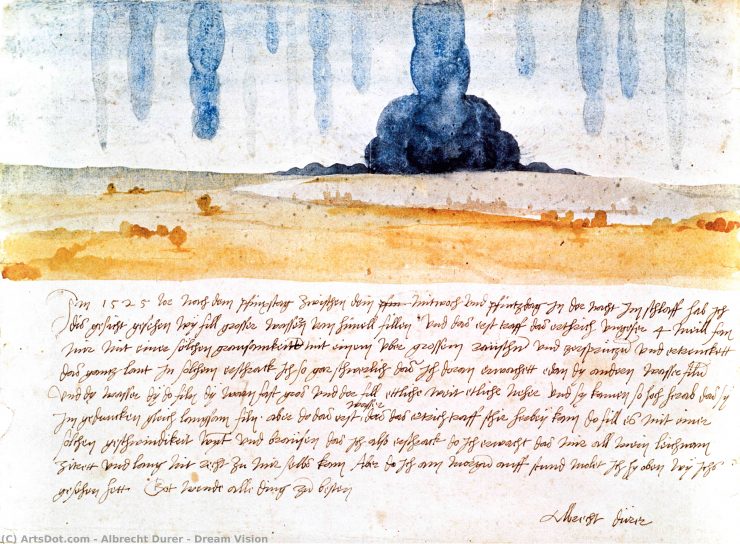

On the other hand, personal dreams will long be seen as pointless, since they are of no use to the community. Moreover, they were associated with madness or mental derangement. This view, deeply rooted in the Middle Ages, continued during the Renaissance, which, although renowned for its humanist philosophy and its emphasis on human individuality, paid little attention to the importance of dreams. This was without counting on Albrecht Dürer who, in 1525, left an exceptional testimony to his curiosity about dreamlike representations. In it, the German artist, who gained international acclaim during his lifetime, depicts a watercolour landscape in which columns of water fall violently from the sky. The commentary left beneath his work suggests that Dürer was terrified, woke up suddenly and decided to depict what he had just seen. Nevertheless, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Cartesian philosophy continued to discredit dream representations. Artists, deeply influenced by classical canons and conventions, continued to illustrate biblical dreams.

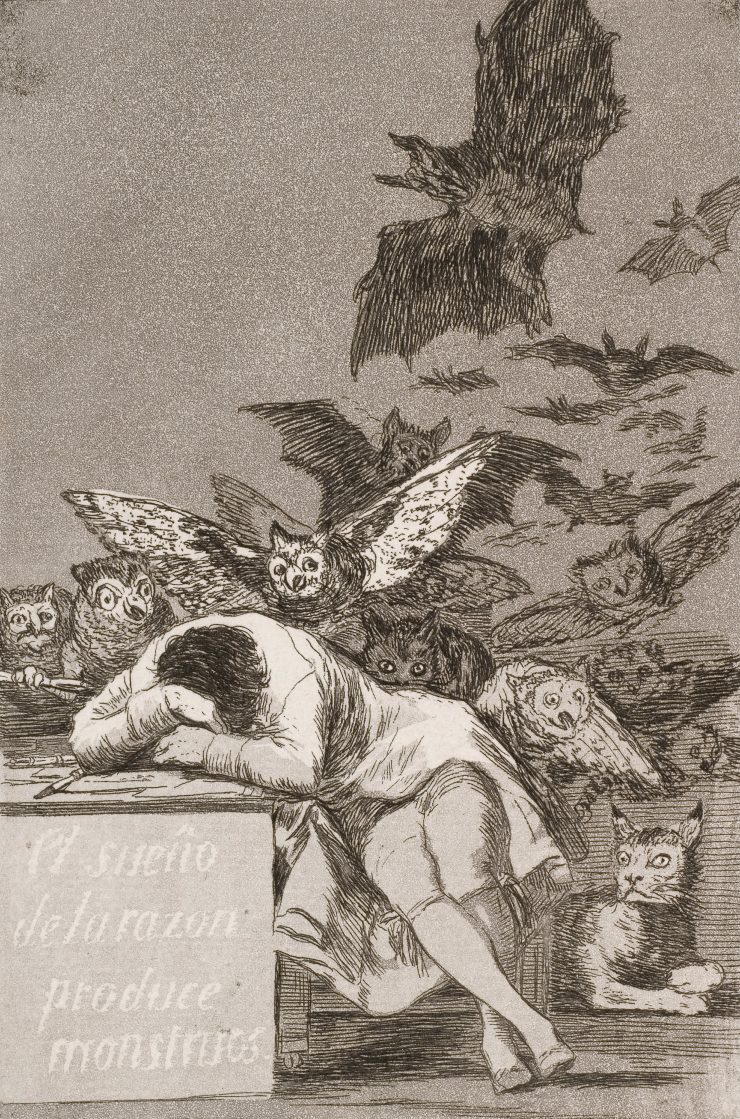

It was not until the nineteenth century that subjectivity became an important feature for artists. Dreams became a favourite theme for self-exploration, and were dubbed “the second world” by the German Romantics. Seen as a means of escaping reality, dreams became a metaphor for poetic solitude, revealing what lies deep within souls, both in literature and in painting. In his work The Dreams of Reason Bring Monsters, Francisco Goya depicts an artist asleep at the side of his instruments. The man is surrounded by flying monsters, which symbolise ignorance and the vices of society.

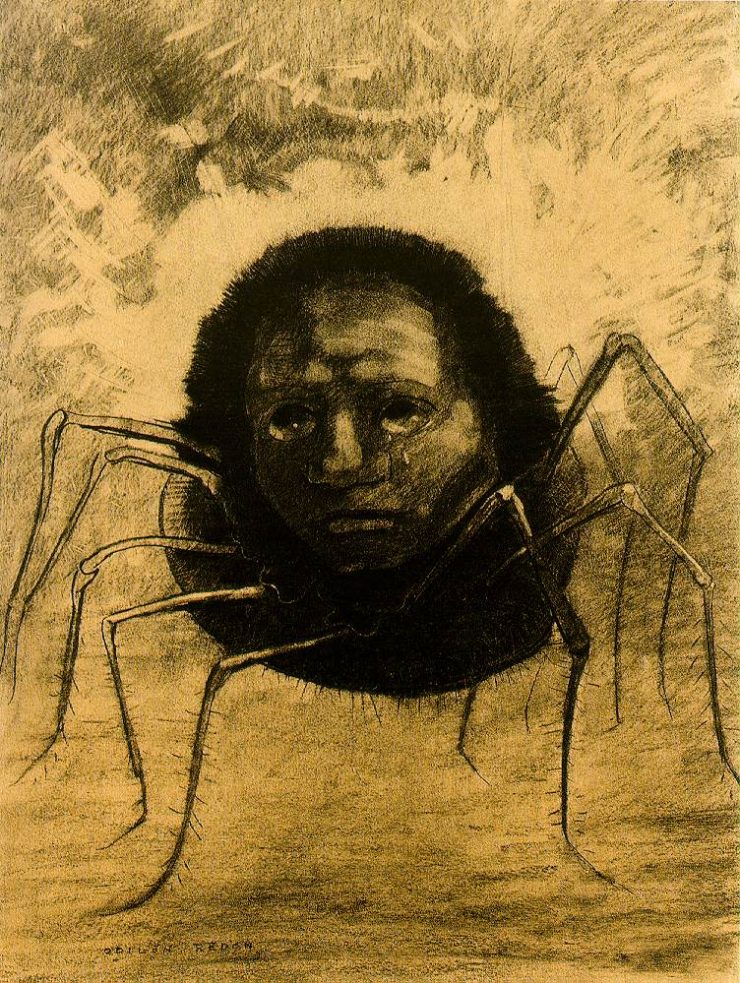

With the emergence of symbolism, dreams were no longer merely aesthetic, but took on the role of a source of creation. This movement, contemporary with psychoanalysis and Freud’s theories, went against naturalism and realism and became the preferred way of representing the mysteries of reality. In this new vision, objects and subjects acquire their meaning only through their symbolism. Odilon Redon, for example, became famous for his explorations of various aspects of thought, from the darker side of the human soul to dream mechanisms. In several of his series, the artist depicts eerie hybrid creatures straight from his imagination, a characteristic that earned him the nickname “Prince of Dreams”.

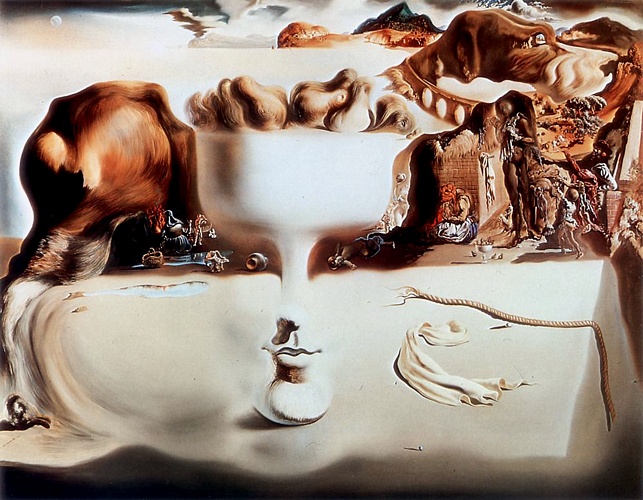

But we can’t talk about dreams without mentioning surrealism. This movement, which emerged in the 1920s, aims to link all the mental states of creation by abolishing the boundaries of reality. Its artists therefore based their interest on hypnosis, spiritualism and sleep – in other words, anything that could bring out the unconscious so that the works could form on their own, without any real control by their creator. The Surrealists achieved this state of semi-consciousness through a number of techniques, such as automatic writing and dream narration, which consisted of describing one’s dream as soon as one woke up, while still in a state of somnolence. Salvador Dali was also at the origin of paranoia-criticism, a practice that aims to represent almost invisible double images that make perception more complex than it first appears. In Apparition d’un visage et d’un compotier sur une plage, the dog’s head in the background is actually made up of mountains, the sea and a tunnel. The collar is represented by a viaduct. Finally, in the centre of the composition, the fruit bowl containing pears reveals the face of a young girl whose eyes are made of shells.

The Surrealists were suggesting that beyond reality, only madness could lead to art. For them, the real and the imaginary collide to form a dream painting that is sometimes surprising, but always deeply symbolic.

Today, dream themes are still used by artists such as Julie Lagier, who draws inspiration from her nightmares to create chimerical moods and atmospheres. She explains: “I’ve chosen to continue dreaming rather than face up to the harsh realities that surround us. I interpret them in this way, with a touch of poetry, sometimes violent, sometimes dreamlike, in a very minimalist way, content with little to say a lot. The artist takes a gentle approach to her disturbing nights, in which she dismembers herself and then reassembles the pieces of her body in the wrong order.

Since the very beginnings of creation, dream painting has been a way of recomposing the world and awakening multiple interpretations within us to help us understand our environment or, conversely, to help us interpret what lies deep within each of us.

DID YOU KNOW?

– The artist Eugène Delacroix was a member of the Haschischins, a group known for using various drugs so that the doctor Moreau de Tour could analyse their dreams and the hallucinations they caused.

– It was when Francisco Goya became totally deaf that his painting became darker and sadder, as can be seen in the Caprichos series, which includes the work Dreams of Reason Bring Monsters.

– Salvador Dali used to say: “Surrealism is me!”