Like France, England and Portugal, Spain was one of Europe’s major colonial powers. After the loss of its territorial possessions in the 19th century, the peninsula was plunged into a period of uncertainty in which its economy and politics were weakened. This instability slowed down the industrialization of the country, which found itself increasingly on the margins of Europe.

These dark years finally gave way, after 1931, to a more stable period with the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the Second Republic. This period saw many fundamental reforms, such as the separation of Church and State, the approval of the Catalan and Basque statutes, the creation of schools and the establishment of an effective cultural policy. Although social tensions reached a peak due to anarchist, Catholic and monarchist protests against the new government, women obtained the right to vote, the right to divorce, the right to abortion and the right to work freely.

It was in this context that the “Sin sombrero” appeared. This group of women, close to the famous Generation of ’27, are today considered the pioneers of Spanish feminism.

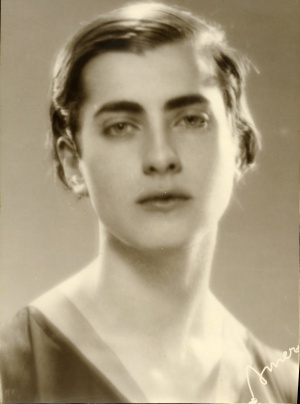

Among them we find poets such as Ernestina de Champourcín, who promoted modernity and social progress in her writings. We should also mention Josefina de la Torre and Concha Méndez who, during her exile in Mexico, opened a printing press in which she published the texts of Spaniards fleeing Franco’s regime. The Sin sombrero women also form part of the field of philosophy through the figure of María Zambrano. She was one of the few women to receive the Prince of Asturias Prize and the Cervantes Prize for her work. In the field of writing, the novelists María Teresa León and Rosa Chacel, whose aim was to promote the place of women in society and to reinforce the idea that art should be at the service of freedom. In the plastic arts, we find the sculptor Marga Gil Roësset and the surrealist painter and woman who gave her name to this group of intellectuals, Maruja Mallo.

All these personalities, although very different and sharing only close relations, were united on certain points. Among them, equal rights and the defense of the individual role of each person, regardless of their sex. They all participated in the feminization of the language, especially in the professional sphere. Under their influence, new terms such as “female writer”, “novelist” or “painter” were normalized.

Undoubtedly, the “Sin Sombrero” women have left their mark by embodying the image of a modern Spain, as well as the image of the emancipated and independent woman.

We can then ask ourselves why this group of avant-garde intellectuals is called “Sin Sombrero”. It is important to note that in late 19th and early 20th century Spain, the wearing of a hat was, for both men and women, a sign of social hierarchy. While men were allowed to escape this rule in enclosed spaces, women were required to wear it in all circumstances. The famous playwright Joaquín Dicenta ended up asking, at the beginning of the 20th century, for permission for women to uncover their heads in theatres so that everyone could have a good view of the stage.

According to some sources, it was Maruja Mallo who one day had the idea of crossing the Puerta del Sol square in Madrid without a hat. This action, considered an act of rebellion against established customs, would define this group of intellectuals.

However, this new freedom was short-lived. When the Civil War broke out in Spain in 1936, Franco came to power and established a dictatorship that would last 36 years. The dictator, who pursued a deeply nationalist and religious ideology, put an end to this new emancipation of women. Women quickly disappeared from the public scene. They came of age at 25 and were soon forced to limit themselves to the role of wives and housewives.

Faced with these changes, the Sin Sombrero women were condemned to exile in other European countries and in America, while in Spain their history, their work and their struggles were ignored and finally almost completely forgotten.