Today, there is still no universal theory of colour. It is difficult to believe that it is possible to develop a single vision or interpretation of colour, since each culture, throughout history, has or has had a chromatic perception linked to its own beliefs and influences.

Science tells us, empirically, that colour is generated by light which, bouncing off the object, creates light waves that the eye can perceive. Colours are therefore, above all, a matter of physical perception. However, in the history of art, colour has long been a tool for representing the world and has finally gained such symbolic power that it will eventually free itself from form and acquire a profound meaning through its own power. This battle between the supremacy of form and colour continues to be debated to this day.

Whereas in antiquity, colour in the arts had only a decorative role, the Middle Ages brought nuance back to the fore. Thanks to its stereotypical representations, the palette became an element that facilitated the reading of images and began to exploit the emotional dimension of its audience. The Virgin Mary, for example, became directly recognisable at this time thanks to her pink and blue habit.

With the Renaissance, and the advent of oil painting, realistic forms took over, leading artists to no longer rely solely on the symbolism of colours, but to use them as a support to sublimate the representations. This is seen in particular in the representations of the sumptuous fabrics that only the great people could afford. This trend, institutionalised by Academism, lasted until the 19th century.

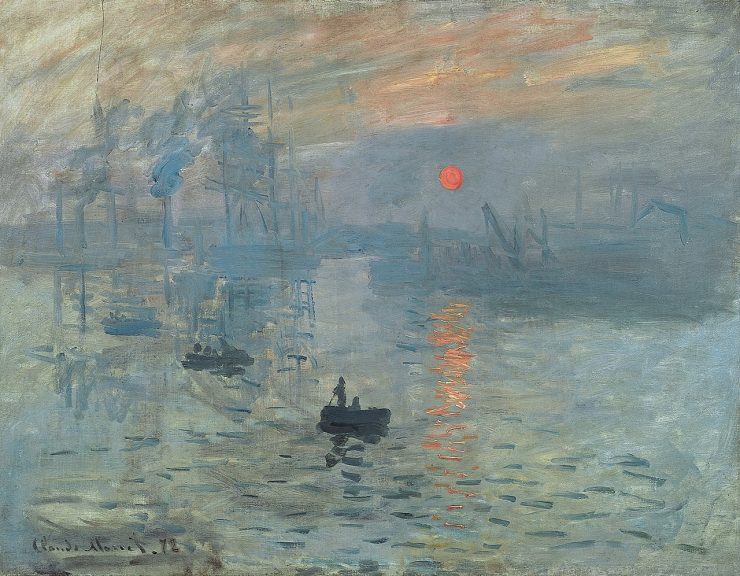

Oscillating between the physical, psychological and symbolic domains, the history of colours is also closely linked to the evolution of techniques. What if we told you that without the invention of the paint tube, there might not have been an avant-garde? Until the 19th century, artists had no choice but to stay in their studios to create their work, but also their palette. Indeed, painters mixed pigments and binders themselves to obtain the shades they wanted to apply to the canvas. As synthetic paint appeared, artists began to take an interest in painting on the ground or in the open air. This was the birth of the first so-called modern movement: impressionism, which would influence all the artistic movements to come.

This is the case, for example, with Fauvism, which, at the beginning of the 20th century, aimed to free the palette from form. Thanks to its bright, garish flat colours, artists like Matisse proposed a new reality, punctuated by emotional and aesthetic chromatic interpretation. This revolution was also accompanied by the German Expressionist movement which, as its name suggests, also developed the exacerbated expression of pure colours. Its greatest representative, Wassily Kandinsky, followed this red line throughout his career, as shown by his abstract and musical works, known for their deeply symbolic chromatic alphabet. Another important theory is that of simultaneous contrast, created by Sonia and Robert Delaunay. These two major figures of the avant-garde, famous for their contribution to the Orphic movement, combined complementary colours to make them more intense and vivid.

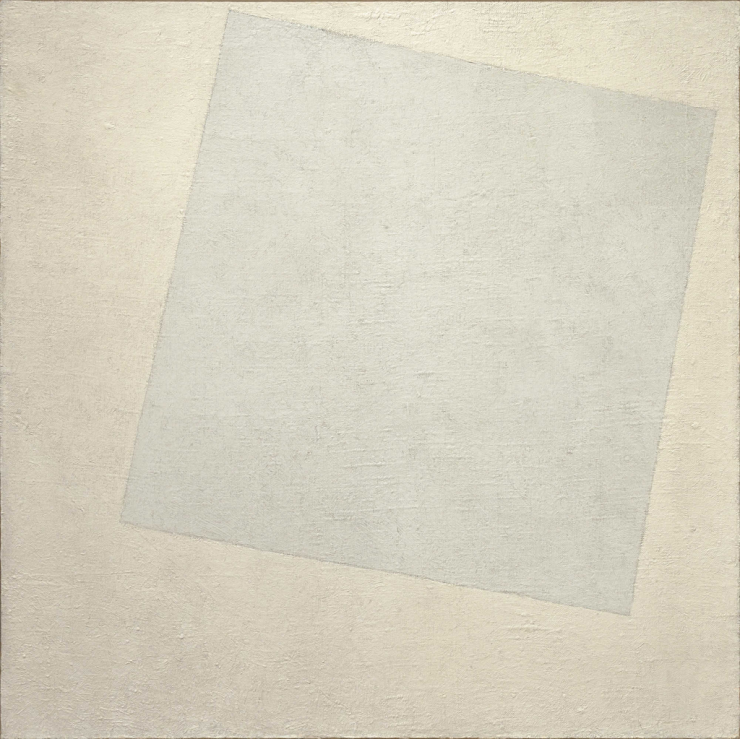

Finally, the twentieth century also saw the first monochromes. These works illustrate not only a total freedom of colour from line, but also an almost total freedom of the artist’s hand, which leaves no visible trace on his canvas. Malevich, with his white square on a white background, was the precursor of this new art form. Later, other painters such as Yves Klein, Ellsworth Kelly and Clément Mosset also gave their single-colour creations a density, materiality and spirituality thanks to the unique force of nuance. This continues to this day, as can be seen in the work of French artist Pierre Soulage, who, with his “outre-noir”, illustrates not only the darkness but also, thanks to the contrast created, the light that can emanate from it.

It seems logical to say that the twentieth century is the advent of colour. Nevertheless, the debate it provokes is, even today, an area that has not found its limit. Artists continue to go further and further in their interest in colour and to renew it.